Screw thread

A screw thread, often shortened to thread, is a helical structure used to convert between rotational and linear movement or force. A screw thread is a ridge wrapped around a cylinder or cone in the form of a helix, with the former being called a straight thread and the latter called a tapered thread. More screw threads are produced each year than any other machine element.[1]

The mechanical advantage of a screw thread depends on its lead, which is the linear distance the screw travels in one revolution.[2] In most applications, the lead of a screw thread is chosen so that friction is sufficient to prevent linear motion being converted to rotary, that is so the screw does not slip even when linear force is applied so long as no external rotational force is present. This characteristic is essential to the vast majority of its uses. The tightening of a fastener's screw thread is comparable to driving a wedge into a gap until it sticks fast through friction and slight plastic deformation.

Contents |

Applications

Screw threads have several applications:

- Fastening

- Fasteners such as wood screws, machine screws, nuts and bolts.

- Connecting threaded pipes and hoses to each other and to caps and fixtures.

- Gear reduction via worm drives

- Moving objects linearly by converting rotary motion to linear motion, as in the leadscrew of a jack.

- Measuring by correlating linear motion to rotary motion (and simultaneously amplifying it), as in a micrometer.

- Both moving objects linearly and simultaneously measuring the movement, combining the two aforementioned functions, as in a leadscrew of a lathe.

In all of these applications, the screw thread has two main functions:

- It converts rotary motion into linear motion.

- It prevents linear motion without the corresponding rotation.

Basic concepts of design

Gender

Every matched pair of threads, external and internal, can be described as male and female. For example, a screw has male threads, while its matching hole (whether in nut or substrate) has female threads. This property is called gender.

Handedness

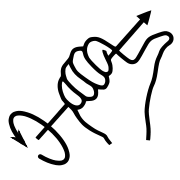

The helix of a thread can twist in two possible directions, which is known as handedness. Most threads are oriented so that a bolt or nut, seen from above, is tightened (the item turned moves away from the viewer) by turning it in a clockwise direction, and loosened (the item moves towards the viewer) by turning anti-clockwise. This is known as a right-handed (RH) thread, because it follows the right hand grip rule (often called, more ambiguously, "the right-hand rule"). Threads oriented in the opposite direction are known as left-handed (LH).

To determine if a particular thread is right or left handed, look straight at the thread. If the helix of the thread is moving up to the right, it is a right-handed thread and conversely up to the left, a left-handed thread. This holds whether the thread is oriented up or down.

By common convention, right-handedness is the default handedness for screw threads. Therefore, most threaded parts and fasteners have right-handed threads. Left-handed thread applications include:

- Where the rotation of a shaft would cause a conventional right-handed nut to loosen rather than to tighten due to fretting induced precession. Examples include:

-

- The left-hand grinding wheel on a bench grinder.

- The lug nuts on the left side of some automobiles.

- In combination with right-handed threads in turnbuckles.

- In some gas supply connections to prevent dangerous misconnections, for example in gas welding the flammable gas supply uses left-handed threads.

- In a threaded joint, in a situation where neither threaded pipe end can be rotated to tighten/loosen the joint, e.g. in traditional heating pipes running through multiple rooms in a building. In such a case, the coupling will have one right-handed and one left-handed thread

- In some instances, for example early ballpoint pens, to provide a "secret" method of disassembly.

- In mechanisms to give a more intuitive action as:

- The leadscrew of the cross slide of a lathe to cause the cross slide to move away from the operator when the leadscrew is turned clockwise.

- The depth of cut screw of a "Stanley" type metal plane (tool) for the blade to move in the direction of a regulating right hand finger.

The term chirality comes from the Greek word for "hand" and concerns handedness in many other contexts.

Form

The cross-sectional shape of a thread is often called its form or threadform (also spelled thread form). It may be square, triangular, trapezoidal, or other shapes. The terms form and threadform sometimes refer to all design aspects taken together (cross-sectional shape, pitch, and diameters).

Most triangular threadforms are based on an isosceles triangle. These are usually called V-threads or vee-threads because of the shape of the letter V. For 60° V-threads, the isosceles triangle is, more specifically, equilateral. For buttress threads, the triangle is scalene.

The theoretical triangle is usually truncated to varying degrees (that is, the tip of the triangle is cut short). A V-thread in which there is no truncation (or a minuscule amount considered negligible) is called a sharp V-thread. Truncation occurs (and is codified in standards) for practical reasons:

- The thread-cutting or thread-forming tool cannot practically have a perfectly sharp point; at some level of magnification, the point is truncated, even if the truncation is very small.

- Too-small truncation is undesirable anyway, because:

- The cutting or forming tool's edge will break too easily;

- The part or fastener's thread crests will have burrs upon cutting, and will be too susceptible to additional future burring resulting from dents (nicks);

- The roots and crests of mating male and female threads need clearance to ensure that the sloped sides of the V meet properly despite (a) error in pitch diameter and (b) dirt and nick-induced burrs.

- The point of the threadform adds little strength to the thread.

Ball screws, whose male-female pairs involve bearing balls in between, show that other variations of form are possible.

Angle

The angle characteristic of the cross-sectional shape is often called the thread angle. For most V-threads, this is standardized as 60 degrees, but any angle can be used.

Lead, pitch, and starts

Lead (pronounced /ˈliːd/) and pitch are closely related concepts. The difference between them can cause confusion, because they are equivalent for most screws. Lead is the distance along the screw's axis that is covered by one complete rotation of the screw (360°). Pitch is the distance from the crest of one thread to the next. Because the vast majority of screw threadforms are single-start threadforms, their lead and pitch are the same. Single-start means that there is only one "ridge" wrapped around the cylinder of the screw's body. Each time that the screw's body rotates one turn (360°), it has advanced axially by the width of one ridge. "Double-start" means that there are two "ridges" wrapped around the cylinder of the screw's body.[4] Each time that the screw's body rotates one turn (360°), it has advanced axially by the width of two ridges. Another way to say the same idea is that lead and pitch are parametrically related, and the parameter that relates them, the number of starts, often has a value of 1, in which case their relationship becomes equivalence.

While specifying the pitch of a metric thread form is common, inch-based standards usually use threads per inch (TPI), which is how many threads occur per inch of axial screw length. Pitch and TPI describe the same underlying physical property—merely in different terms. When units of measurement are constant TPI is the reciprocal of pitch and vice versa. For example, a 1⁄4-20 thread has 20 TPI, which means that its pitch is 1⁄20 inch (0.050").

Coarse versus fine

Coarse threads are those with larger pitch (fewer threads per axial distance), and fine threads are those with smaller pitch (more threads per axial distance). Coarse threads have a larger threadform relative to screw diameter, whereas fine threads have a smaller threadform relative to screw diameter. This distinction is analogous to that between coarse teeth and fine teeth on a saw or file, or between coarse grit and fine grit on sandpaper.

The common V-thread standards (ISO 261 and Unified Thread Standard) include a coarse pitch and a fine pitch for each major diameter. For example, 1⁄2-13 belongs to the UNC series (Unified National Coarse) and 1⁄2-20 belongs to the UNF series (Unified National Fine).

A common misconception among people not familiar with engineering or machining is that the term coarse implies here lower quality and the term fine implies higher quality. The terms when used in reference to screw thread pitch have nothing to do with the tolerances used (degree of precision) or the amount of craftsmanship, quality, or cost. They simply refer to the size of the threads relative to the screw diameter. Coarse threads can be made accurately, or fine threads inaccurately.

Diameters

There are several relevant diameters for screw threads: major diameter, minor diameter, and pitch diameter.

Major diameter

Major diameter is the largest diameter of the thread. For a male thread, this means "outside diameter", but in careful usage the better term is "major diameter", since the underlying physical property being referred to is independent of the male/female context. On a female thread, the major diameter is not on the "outside". The terms "inside" and "outside" invite confusion, whereas the terms "major" and "minor" are always unambiguous.

Minor diameter

Minor diameter is the smallest diameter of the thread.

Pitch diameter

Pitch diameter, also known as mean diameter, is a diameter in between major and minor. It is the diameter at which each pitch is equally divided between the mating male and female threads. It is important to the fit between male and female threads, because a thread can be cut to various depths in between the major and minor diameters, with the roots and crests of the threadform being variously truncated, but male and female threads will only mate properly if their sloping sides are in contact, and that contact can only happen if the pitch diameters of male and female threads match closely. Another way to think of pitch diameter is "the diameter on which male and female should meet".

Thread pitch diameter is analogous to gear pitch diameter, which is related to how two mating gears should meet.

Classes of fit

The way in which male and female fit together, including play and friction, is classified (categorized) in thread standards. Achieving a certain class of fit requires the ability to work within tolerance ranges for dimension (size) and surface finish. Defining and achieving classes of fit are important for interchangeability.

Standardization and interchangeability

To achieve a predictably successful mating of male and female threads and assured interchangeability between males and between females, standards for form, size, and finish must exist and be followed. Standardization of threads is discussed below.

Thread depth

Screw threads are almost never made perfectly sharp (no truncation at the crest or root), but instead are truncated, which is known as the thread depth or percentage of thread. The UTS and ISO standards codify the amount of truncation, including tolerance ranges.

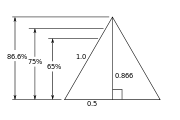

A perfectly sharp 60° V-thread will have a depth of thread ("height" from root to crest) equal to 86.6% of the pitch. This fact is intrinsic to the geometry of an equilateral triangle—a direct result of the basic trigonometric functions. It is independent of measurement units (inch vs mm).

The typical depth of UTS and ISO threads with truncation included is around 75% of the pitch. Threads can be (and often are) truncated a bit more, yielding thread depths of 60% to 65%. This makes the thread-cutting easier (yielding shorter cycle times and longer tap and die life) without a large sacrifice in thread strength. For many applications, 60% threads are optimal, and 75% threads are wasteful or "over-engineered" (additional resources were unnecessarily invested in creating them). To truncate the threads further different techniques are used for male and female threads. For male threads, the bar stock is "turned down" some before thread cutting, so that the major diameter is reduced. Likewise, for female threads the stock material is drilled with a slightly larger tap drill, reducing the minor diameter. The pitch diameter is unchanged by these operations which change material dimensions prior to tapping (thread cutting).

This balancing of truncation versus thread strength is common to many engineering decisions involving material strength and material thickness, cost, and weight. Engineers use a number called the safety factor to quantify the increased material thicknesses or other dimension beyond the minimum required for the estimated loads on a mechanical part. Increasing the safety factor generally increases the cost of manufacture and decreases the likelihood of a failure. So the safety factor is often the focus of a business management decision when a mechanical product's cost impacts business performance and failure of the product could jeopardize human life or company reputation. For example, aerospace contractors are particularly rigorous in the analysis and implementation of Safety factors in the manufacture of manned space flight equipment or even launch equipment for unmanned satellites. Material thickness affects not only cost, but the weight and the cost to lift that weight into orbit. The cost of failure and the cost of manufacture are both extremely high. Thus the safety factor dramatically impacts company fortunes and is often worth the additional engineering expense required for detailed analysis and implementation. The fate of extremely expensive space hardware often hangs on the thread depth for bolts used in the mounting of the hardware to space launch vehicles.

Standardization

Standardization of screw threads has evolved since the early nineteenth century to facilitate compatibility between different manufacturers and users. The standardization process is still ongoing; in particular there are still (otherwise identical) competing metric and inch-sized thread standards widely used.[5] Standard threads are commonly identified by short letter codes (M, UNC, etc.) which also form the prefix of the standardized designations of individual threads.

Additional product standards identify preferred thread sizes for screws and nuts, as well as corresponding bolt head and nut sizes, to facilitate compatibility between spanners (wrenches) and other tools.

ISO standard threads

The most common threads in use are the ISO metric screw threads (M) for most purposes and BSP threads (R, G) for pipes.

These were standardized by the International Organization for Standardization in 1947. Although metric threads were mostly unified in 1898 by the International Congress for the standardization of screw threads, separate metric thread standards were used in France, Germany, and Japan, and the Swiss had a set of threads for watches.

Other current standards

In particular applications and certain regions, threads other than the ISO metric screw threads remain commonly used, sometimes because of special application requirements, but mostly for reasons of backwards compatibility:

- Unified Thread Standard, (UTS), which is still the dominant thread type in the United States and Canada. This standard includes:

- Unified Coarse (UNC), commonly referred to as "National Coarse" or "NC" in retailing.

- Unified Fine (UNF), commonly referred to as "National Fine" or "NF" in retailing.

- Unified Extra Fine (UNEF)

- Unified Special (UNS)

- National pipe thread (NPT), used for plumbing of water and gas pipes, and threaded electrical conduit.

- NPTF (National Pipe Thread Fuel)

- British Standard Whitworth (BSW), and for other Whitworth threads including:

- British Standard Fine (BSF)

- Cycle Engineers' Institute (CEI) or British Standard Cycle (BSC)

- British standard pipe thread (BSP)

- British Standard Pipe Taper (BSPT)

- British Association screw threads (BA), primarily electronic/electrical, moving coil meters and to mount optical lenses

- British standard pipe thread (BSP) which exists in a taper and non taper variant; used for other purposes as well

- BSC (British Standard Cycle) a 26tpi thread form

- British Standard Buttress Threads (BS 1657:1950)

- British Standard for Spark Plugs BS 45:1972

- British Standard Brass a fixed pitch 26tpi thread

- Power screw threads

- Acme thread form

- Square thread form

- Buttress thread

- Camera case screws, used to mount a camera on a photographic tripod:

- ¼″ British Standard Whitworth (BSW) used on almost all small cameras

- ⅜″ BSW for larger (and some older small) cameras

- Royal Microscopical Society (RMS) thread, a special 0.8"-36 thread used for microscope objective lenses.

- Microphone stands:

- ⅝″ 27 threads per inch (tpi) Unified Special thread (UNS, USA and the rest of the world)

- ¼″ BSW (not common in the USA, used in the rest of the world)

- ⅜″ BSW (not common in the USA, used in the rest of the world)

- Stage lighting suspension bolts (in some countries only; some have gone entirely metric, others such as Australia have reverted to the BSW threads, or have never fully converted):

- ⅜″ BSW for lighter luminaires

- ½″ BSW for heavier luminaires

- Tapping screw threads (ST) – ISO 1478

- Aerospace inch threads (UNJ) – ISO 3161

- Aerospace metric threads (MJ) – ISO 5855

- Tyre valve threads (V) – ISO 4570

- Metal bone screws (HA, HB) – ISO 5835

- Panzergewinde (Pg) (German: "Panzer-Gewinde") is an old German 80° thread (DIN 40430) that remained in use until 2000 in some electrical installation accessories in Germany.

- Fahrradgewinde (Fg) (English: bicycle thread) is a German bicycle thread standard (per DIN 79012 and DIN 13.1), which encompasses a lot of CEI and BSC threads as used on cycles and mopeds everywhere (http://www.fahrradmonteur.de/fahrradgewinde.php)

- CEI (Cycle Engineers Institute, used on bicycles in Britain and possibly elsewhere)

- Edison base lamp holder screw thread

- Fire hose connection (NFPA standard 194)

- Hose Coupling Screw Threads (ANSI B2.4-1966) for garden hoses and accessories

- Lowenhertz thread, a German metric thread used for measuring instruments[6]

- Society Thread, a 36 threads/inch Whitworth form standarded by the Royal Microscopical Society of London for microscope objective lenses.

History of standardization

The first historically important intra-company standardization of screw threads began with Henry Maudslay around 1800, when the modern screw-cutting lathe made interchangeable screws a practical commodity. During the next 40 years, standardization continued to occur on the intra-company and inter-company level.[7] No doubt many mechanics of the era participated in this zeitgeist; Joseph Clement was one of those whom history has noted. In 1841, Joseph Whitworth created a design that, through its adoption by many British railroad companies, became a national standard for the United Kingdom called British Standard Whitworth. During the 1840s through 1860s, this standard was often used in the United States and Canada as well, in addition to myriad intra- and inter-company standards. In April 1864, William Sellers presented a paper to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, proposing a new standard to replace the U.S.'s poorly standardized screw thread practice. Sellers simplified the Whitworth design by adopting a thread profile of 60° and a flattened tip (in contrast to Whitworth's 55° angle and rounded tip).[8][9] The 60° angle was already in common use in America,[10] but Sellers's system promised to make it and all other details of threadform consistent.

The Sellers thread, easier for ordinary machinists to produce, became an important standard in the U.S. during the late 1860s and early 1870s, when it was chosen as a standard for work done under U.S. government contracts, and it was also adopted as a standard by highly influential railroad industry corporations such as the Baldwin Locomotive Works and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Other corporations adopted it, and it soon became a national standard for the U.S.,[10] later becoming generally known as the United States Standard thread. Over the next 30 years the standard was further defined and extended and evolved into a set of standards including National Coarse (NC), National Fine (NF), and National Pipe Taper (NPT).

During this era, in continental Europe, the British and American threadforms were well known, but also various metric thread standards were evolving, which usually employed 60° profiles. Some of these evolved into national or quasi-national standards. They were mostly unified in 1898 by the International Congress for the standardization of screw threads at Zurich, which defined the new international metric thread standards as having the same profile as the Sellers thread, but with metric sizes. Efforts were made in the early 20th century to convince the governments of the U.S., UK, and Canada to adopt these international thread standards and the metric system in general, but they were defeated with arguments that the capital cost of the necessary retooling would damage corporations and hamper the economy. (The mixed use of dueling inch and metric standards has since cost much, much more, but the bearing of these costs has been more distributed across national and global economies rather than being borne up front by particular governments or corporations, which helps explain the lobbying efforts.)

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, engineers found that ensuring the reliable interchangeability of screw threads was a multi-faceted and challenging task that was not as simple as just standardizing the major diameter and pitch for a certain thread. It was during this era that more complicated analyses made clear the importance of variables such as pitch diameter and surface finish.

A tremendous amount of engineering work was done throughout World War I and the following interwar period in pursuit of reliable interchangeability. Classes of fit were standardized, and new ways of generating and inspecting screw threads were developed (such as production thread-grinding machines and optical comparators). Therefore, in theory, one might expect that by the start of World War II, the problem of screw thread interchangeability would have already been completely solved. Unfortunately, this proved to be false. Intranational interchangeability was widespread, but international interchangeability was less so. Problems with lack of interchangeability among American, Canadian, and British parts during World War II led to an effort to unify the inch-based standards among these closely allied nations, and the Unified Thread Standard was adopted by the Screw Thread Standardization Committees of Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States on November 18, 1949 in Washington, D.C., with the hope that they would be adopted universally. (The original UTS standard may be found in ASA (now ANSI) publication, Vol. 1, 1949.) UTS consists of Unified Coarse (UNC), Unified Fine (UNF), Unified Extra Fine (UNEF) and Unified Special (UNS). The standard was not widely taken up in the UK, where many companies continued to use the UK's own British Association (BA) standard.

However, internationally, the metric system was eclipsing inch-based measurement units. In 1947, the International Organization for Standardization (interlingually known as ISO) had been founded; and in 1960, the metric-based International System of Units (abbreviated SI from the French Système International) was created. With continental Europe and much of the rest of the world turning to SI and the ISO metric screw thread, the UK gradually leaned in the same direction. The ISO metric screw thread is now the standard that has been adopted worldwide and has mostly displaced all former standards, including UTS. In the U.S., where UTS is still prevalent, over 40% of products contain at least some ISO metric screw threads. The UK has completely abandoned its commitment to UTS in favour of the ISO metric threads, and Canada is in between. Globalization of industries produces market pressure in favor of phasing out minority standards. A good example is the automotive industry; U.S. auto parts factories long ago developed the ability to conform to the ISO standards, and today very few parts for new cars retain inch-based sizes, regardless of being made in the U.S.

Engineering drawing

In American engineering drawings, ANSI Y14.6 defines standards for indicating threaded parts. Parts are indicated by their nominal diameter (the nominal major diameter of the screw threads), pitch (number of threads per inch), and the class of fit for the thread. For example, “.750-10UNC-2A” is male (A) with a nominal major diameter of 0.750 in, 10 threads per inch, and a class-2 fit; “.500-20UNF-1B” would be female (B) with a 0.500 in nominal major diameter, 20 threads per inch, and a class-1 fit. An arrow points from this designation to the surface in question.[11]

Generating screw threads

There are many ways to generate a screw thread including: cutting, casting, forming, grinding, lapping, and rolling.

Examples

Examples of screw threads include:

- Fasteners:

- Wood screws.

- Nuts and bolts, machine screws, cap screws.

- C-clamps.

- Threaded pipe fittings.

- Threaded attachments used to mount equipment on stands, such as:

- The case screw used to mount a camera on a photographic tripod.

- The thread used to mount a microphone or microphone cradle on a microphone stand.

See also

- Unified Thread Standard

- ISO metric screw thread

- National Thread Form

- Acme Thread Form

- Buttress Thread Form

- National Pipe Thread Form

- Dryseal Pipe Threads Form

- Hose Coupling Screw Thread Form

- Metric: M Profile Thread Form

- Metric: MJ Profile Thread Form

- Joseph Whitworth

- British Association screw threads (BA)

Notes

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 741.

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=IRdIAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA137

- ↑ Brown, Sheldon. "Bicycle Glossary: Pedal". Sheldon Brown. http://www.sheldonbrown.com/gloss_p.html#pedal. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- ↑ Bhandari, p. 205.

- ↑ Ryffel 1988, p. 1603.

- ↑ Roe 1916, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ ASME 125th Anniversary: Special 2005 Designation of Landmarks: Profound Influences in Our Lives: The United States Standard Screw Threads

- ↑ Roe 1916, pp. 248-249.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Roe 1916, p. 249.

- ↑ Wilson pp. 77–78 (page numbers may be from an earlier edition).

References

- Bhandari, V B (2007), Design of Machine Elements, Tata McGraw-Hill, ISBN 9780070611412, http://books.google.com/?id=f5Eit2FZe_cC.

- Degarmo, E. Paul; Black, J T.; Kohser, Ronald A. (2003), Materials and Processes in Manufacturing (9th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 0-471-65653-4.

- Green, Robert E. et al. (eds) (1996), Machinery's Handbook (25 ed.), New York, NY, USA: Industrial Press, ISBN 978-0-8311-2575-2.

- Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press, LCCN 16-011753, http://books.google.com/books?id=X-EJAAAAIAAJ&printsec=titlepage. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-024075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, IL, USA (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

- Wilson, Bruce A. (2004), Design Dimensioning and Tolerancing (4th ed.), Goodheart-Wilcox, ISBN 1-59070-328-6.

External links